1 Introduction

This report seeks to aid those in the housing sector in Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland) and Te Tai Tokerau (Northland), to identify opportunities for engagement, investment and greater impact. It has been adapted from a 2020 report for Foundation North.

While the focus is on housing in Te Tai Tokerau and Tāmaki Makaurau, some insights are offered on housing needs, opportunities, issues and policies in Aotearoa New Zealand overall.

A review of information on New Zealand’s housing landscape was undertaken, with a focus on Auckland and Northland. Interviews also occurred with five stakeholders who are well positioned to offer insights regarding Te Tai Tokerau (see section 4.7).

Part 1 provides an overview of homelessness in Auckland, Northland and New Zealand overall. It presents a ‘housing continuum’ of housing options available, from emergency housing to private ownership. It outlines characteristics of the different housing types and how they are provided, alongside examples of service providers.

Part 2 summarises the current housing policies of local and central government and the investment approaches they take.

Part 3 offers a data snapshot of Tāmaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau’s communities and their housing needs.

Part 4 outlines housing opportunities and solutions for these regions.

2 COVID19 and the May 2020 budget

The COVID19 pandemic occurred after this report was initially developed. The impacts of the pandemic on the housing issues in this report will be substantial. The 14 May 2020 government budget contained these broad announcements for housing:

- 8,000 additional public or transitional housing places over the next four to five years.

- $670 million of support and services to tenants.

- Support for housing development and construction, including in the private residential market, to be the subject of further investment.

Continuing to grow the workforce to increase housing supply and meet other housing goals was also signalled. In New Zealand’s dynamic housing space, the hope is that the pandemic will catalyse further urgent action on the issues raised in this report.

3 Key Messages

A solvable crisis

- New Zealand is experiencing an escalating yet solvable housing crisis, the impacts of which are being disproportionately felt by our Pacific and Māori communities. A significant number of children, young people, disabled people and older people are also seriously affected.

- Resolving this situation requires action throughout the housing continuum, and a holistic approach from prevention and early intervention to crisis responses.

- Homelessness is preventable and should be ‘rare, brief and non-recurring’, but providing housing alone will not address its causes.

- Some organisations in Auckland and Northland have developed innovative and high-quality solutions to social housing needs and homelessness. These need support, and there is a will to do more at scale and pace through collaboration and partnering.

- There is increasing evidence of shared leadership and collaboration in the housing sector. For example, Community Housing Aotearoa represents 90 developers, consultants and local councils that between them house about 25,000 people in 13,000 homes in New Zealand.

- Improvements in the quality and standards of building practice and service delivery in the housing sector are becoming evident. Government and other agencies are increasingly collaborating to achieve collective impact.

Housing and government

- The government sector under the Labour Led Coalition has a focus on wellbeing and poverty reduction.

- The Government realises it cannot solve the housing crisis alone, and that solutions for Māori and Pacific must be prioritised.

- The current response to emergency housing, including funding people to stay in motels, is not coping with the rising demand for emergency accommodation. This situation is unsustainable and illustrates the precarious nature of housing for many people, including those who are homeless.

- New government agencies, legislation and programme investments are being established to improve housing in New Zealand.

Housing opportunities

- Housing has a significant influence on individuals’ and populations’ health and wellbeing.

- There are opportunities to improve the housing situation through:

- Increasing housing supply, quality and affordability and the provision of wrap-around services to those experiencing the impacts of the housing crisis most severely (data clearly identifies these people and their localities).

- Supporting iwi/Māori and community providers to strengthen, scale and connect with each other on needs such as housing finance, organisational capacity-building and compliance capabilities.

- Supporting collaborative action to end homelessness. For example, Housing First in Tāmaki Makaurau comprises five organisations that are working together to end homelessness.

- Supporting the building of more social housing and a diverse housing stock.

- Improving housing quality and efficiency for low-income households, for example through the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority’s (EECA’s) insulation scheme.

- Supporting the efforts of innovators, leaders and effective operators, including papakāinga 2 housing providers and initiatives such as the tiny-home building project instigated by Kamo High School students.

- Supporting housing models and types that meet diverse cultural, household type and accessibility needs.

- Listening, building relationships, engaging well and seeking to understand cultural nuances and aspirations.

2 Housing on Māori ancestral land.

3.1. Homelessness and housing needs

1.1 Housing and wellbeing

Providing people with access to safe, warm, stable and secure homes meets a basic need that underpins their personal wellbeing at all stages of their lives. It enables them to achieve a higher quality of life than might otherwise be possible – through having better access to basic services, opportunities to build good relationships with family, neighbours and communities, and the ability to maintain their independence.

Kāinga

For Māori, kāinga is a fundamental principle for housing and wellbeing. Having a warm, dry and safe place to call home is not just about a building or shelter; it supports connections to land and whānau (Kake, 2019).

1.2 Homelessness

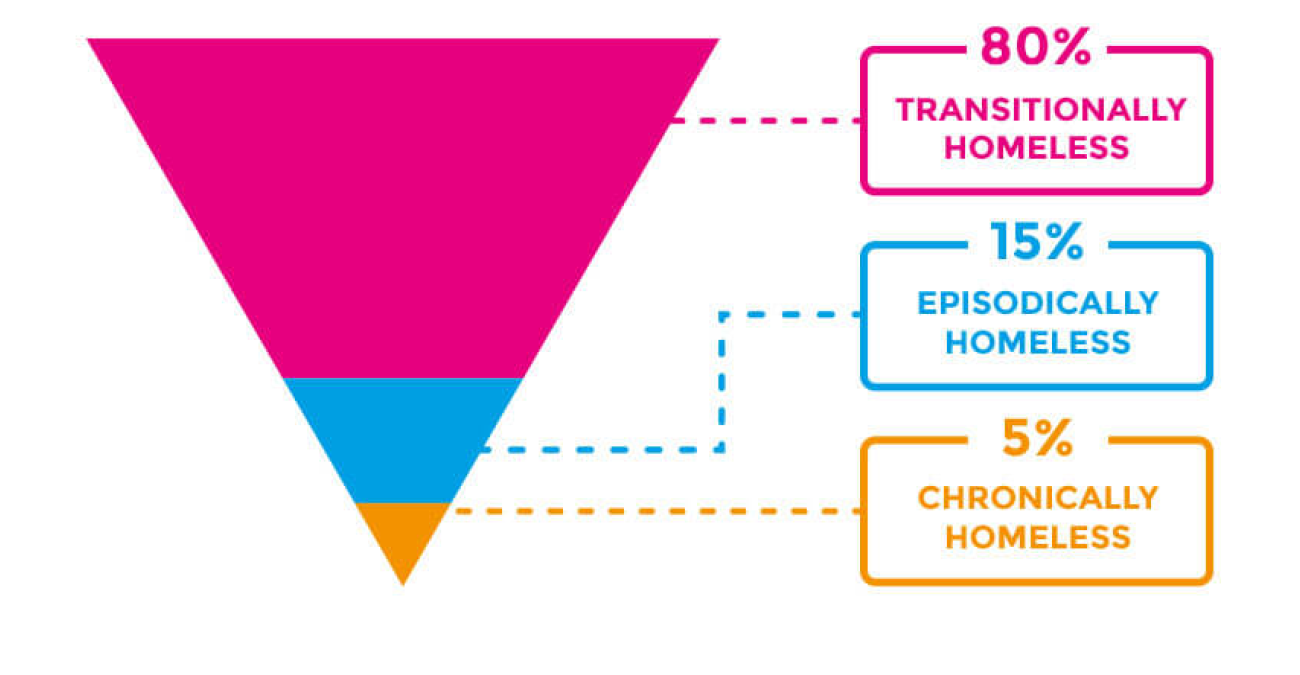

There are three main types of homelessness – transitional, episodic and chronic.

Transitional homelessness can be short term and is caused by a variety of issues, including redundancy, relationship or family breakdowns and health issues. Families are the most likely to experience transitional homelessness, and for many it is their first encounter with social services.

Episodic homelessness can be linked to other issues including addiction, trauma, mental health issues and debt, which may be a result of long-term reliance on benefits or poor financial literacy.

Chronically homeless people include rough sleepers. They may spend years being homeless due to multiple and complex needs. However, while people experiencing chronic homelessness are the most visible, they are a minority group, making up just 5% of the homeless population (see Figure 1).

Evidence suggests that rapid rehousing should be the priority for people who are transitionally or episodically homeless. In Tāmaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau, a lack of suitable housing for these people has created a pressure point for emergency and social housing providers.

Of all the OECD member countries, New Zealand has one of the highest incidence rates of homelessness in its population.1 The number of homeless people in Tāmaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau is growing, which has led to increased attention on crisis response services and models such as Housing First.

An Auckland Council report (2017) recommended a “broader than crisis response” approach –including prevention and early intervention – to make homelessness “rare, brief and non-recurring”. The report noted that more than 20,000 people were living in precarious housing in Auckland, including uninhabitable housing.2

1OECD data, released on 19 December 2019, reports that New Zealand has a 0.94% incidence of homelessness of the total population – Australia’s is 0.48%. This is partly explained by the fact that both countries have adopted a broad definition of homelessness.

- Nearly 50% of all New Zealanders who are homeless are in Auckland.

- A 23% increase in youth homelessness was reported in New Zealand between 2006 and 2013 (using census data).

- Family homelessness in New Zealand increased by 44% between 2006 and 2013, representing nearly 21,800 individuals in 2013.

Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/els/family/HC3-1-Homeless-population.pdf.

2Auckland Council (August 2017). Auckland Council’s position and role in improving, ending and preventing homelessness. Report to Environment and Community Committee, August 2017. Retrieved from Auckland Council.

1.3 The housing continuum

The housing continuum illustrates the different housing types available to people in New Zealand (see Figure 2). If their circumstances change people may move around the housing continuum and require increased or decreased support to do so. In Tāmaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau, the lack of affordable houses and rental accommodation is placing pressure on all parts of the housing continuum.

Each component of the continuum has an important role in meeting New Zealand’s housing needs. In general, the highest levels of government subsidy and wrap-around support are required at the left-hand end.

Table 1 looks at each housing type, providing details of the key system ‘actors’, such as government initiatives, and examples of community providers and models/approaches.

Housing needs in Tāmaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau require a joined-up housing continuum, in both urban and rural environments.

Housing type | Description and key characteristics | Examples |

| EMERGENCY HOUSING |

|

|

| SOCIAL HOUSING |

|

|

| ASSISTED RENTAL HOUSING |

|

|

| ASSISTED OWNERSHIP |

|

|

| PRIVATE OWNERSHIP AND PRIVATE RENTAL ACCOMMODATION |

|

|

3.2. Government roles

The Government has been involved with the housing sector since New Zealand’s first state-housing programme began in 1936. This section summarises its current policies and investment in housing – with new housing agencies, legislation and investments driving the delivery of government housing and wellbeing policy agendas.

2.1 Key government agencies and programmes

Ministry of Housing and Urban Development

The Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) was established in October 2018, combining functions from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) and MSD, along with the monitoring of Kāinga Ora.

HUD works with other central and local government agencies, the housing sector, communities and iwi, and is responsible for leading New Zealand’s housing and urban development work programme. This programme includes strategy, policy, funding and the monitoring and regulation of New Zealand’s housing and urban development systems.

HUD’s strategic priorities include:

- Addressing homelessness.

- Increasing public and private housing supply.

- Modernising rental laws and rental standards.

- Increasing access to affordable housing for people to rent and buy.

- Supporting quality urban development and thriving communities.

HUD publishes a housing dashboard report, which outlines the national housing situation, outputs and results (current at November 2019).

Housing First

Housing First is HUD’s flagship programme for homelessness. It aims to move rough sleepers quickly into appropriate housing and immediately provides tailored, wrap-around services to address the issues that led to their homelessness. International evidence shows that 80% of people who receive Housing First services retain their housing and do not return to homelessness.

In Tāmaki Makaurau in 2017, 150 homeless people were helped into housing during the first months of a collaboration between the Government and Housing First. Two years later Housing First reported having housed 1,078 families in total, including 500 children.

In 2019 the Government Budget committed $63.4 million to Northland, with the aim of enabling Housing First delivery through Kāinga Pūmanawa, a collective in Whāngārei made up of the Ngāti Hine Health Trust, One Double Five Community Trust and Kāhui Tū Kaha.

The Aotearoa New Zealand Homelessness Action Plan (2020-2023) provides a framework with actions to improve the wellbeing and housing outcomes of individuals and whānau who are at risk of, or experiencing, homelessness.

Kāinga Ora—homes and communities

Kāinga Ora was established in October 2019 and comprises the former Housing New Zealand and its subsidiary Homes, Land, Community, and KiwiBuild.

Kāinga Ora’s dual roles involve being a public housing landlord and a partner in enabling, facilitating and building urban development projects. HUD’s most recent housing supply quarterly report states that 62,901 state houses are provided by Kāinga Ora and 6,708 community houses are provided by 37 registered Community Housing Providers throughout New Zealand. KiwiBuild was announced in 2017 as a Government commitment to build 100,000 affordable homes in 10 years. However, leadership and delivery challenges led to the programme target being reset in October 2019.

KiwiBuild now includes shared-ownership schemes. It aims to work with the building sector to facilitate new housing development by:

- Reducing risk by underwriting homes in new developments.

- Making land available for development.

- Integrating affordable housing into major urban development projects.

Developers partnering with the KiwiBuild programme are required to offer portions of the homes to eligible KiwiBuild buyers first.

Ministry of Health

The Healthy Homes Initiative is a partnership between the Ministry of Health, Kāinga Ora, EECA, the Warmer Kiwi Homes programme and MBIE. It provides housing enhancements to improve health outcomes and energy efficiency in low-income households.

Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority

Six percent of New Zealand’s energy-related emissions come from the residential sector. EECA’s primary purpose is to mobilise New Zealanders to be “clean and clever leaders in energy use”.

Launched in 2018, Warmer Kiwi Homes is a four-year government programme that offers grants covering two-thirds of the cost of an efficient wood burner, pellet burner or heat pump (capped at $2,500), as well as ceiling and underfloor insulation. Eligible recipients include Community Services Card holders and people living in areas with deprivation index scores of 8, 9 or 10 (most deprived).

The insulation must meet BRANZ’s quality standards, and its installation is audited by EECA as part of its provider management system. Research indicates that the health and wellbeing returns on housing insulation for low-income households can be as high as 6:1 per dollar invested.

He Kāinga Oranga (the Housing and Health Research Programme) and Motu Economic and Public Policy Research have shown that the health benefits for adults exceed the costs by a factor of nearly 4:1 and, for children, 6:1. Other benefits include employment and training in retrofitting and insulation, and energy savings.

Ministry of Social Development

MSD is responsible for Work and Income’s allocation of benefits and allowances. As noted earlier, this includes managing the Housing Register and special housing allowances such as Emergency Housing Special Needs Grants.

MSD’s January 2020 fact sheet reported that the number of grants for Accommodation Supplements and Emergency Housing Special Needs Grants had increased five-fold in the previous two years and totalled $48 million in the December 2019 quarter.

Some MSD functions, such as reporting on the Housing Register (the demand for accommodation and housing and the support provided, including Emergency Housing Special Needs Grants), are moving to HUD.

MSD also funds non-government organisations (NGOs) that support other parts of the housing system, such as Orange Sky, which provides mobile laundry and shower facilities to homeless people in Tāmaki Makaurau.

Te Puni Kōkiri

Te Puni Kōkiri is responsible for the Māori Housing Network. The Network’s role includes:

- Enabling iwi and other Māori organisations to improve the quality of housing for whānau.

- Building the Māori housing sector’s capability.

- Increasing affordable housing supply for whānau.

- Supporting Māori emergency housing providers.

Northland received 22% of the Māori Housing Network allocated funds in the last financial cycle.

2.2 Government legislation

Table 2 summarises key legislation enacted in the past year to support the Government’s new housing directions.

Table 2: Housing sector legislation 2019

Legislation | Summary |

| The Residential Tenancies Amendment Act 2019 |

|

| The Residential Tenancies (Healthy Homes Standards) Regulations 2019 |

|

| The Kāinga Ora—Homes and Communities Act 2019 |

|

| The Urban Development Bill |

|

| The Child Poverty Reduction Act 2018 |

|

3.3. Regional data snapshots

3.1 Groups with high needs for housing equity

Evidence of housing inequality in Tāmaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau has attracted government, council and community attention, as housing affordability decreases and support systems become increasingly stretched. There is a need for resources and capability-building for community housing organisations led by and for Māori, Pacific and ethnic communities. Existing organisations have a strong focus on equity and cultural responsiveness and want to be more effective in their work.

Māori and Pacific households are most affected by the housing crisis’s contribution to growing inequalities, partly because the crisis is denying low-income families opportunities to acquire asset bases. The falling rates of home ownership since the early 1990s, for Māori and Pacific particularly, mean a large numbers of renters will move into retirement without secure housing (Barber, 2019). Addressing the housing needs of Māori and Pacific is an essential part of an effective response to community housing needs.

Ethnic communities, young people and the elderly are often the invisible faces of homelessness. Ethnic communities are a growing demographic group, particularly in the Tāmaki Makaurau region, and can struggle to find affordable housing in a competitive market that is often discriminatory. In 2018 the Chinese New Settlers Services Trust opened 36 public housing units in Panmure for Asian seniors. The development included a partnership with MBIE and MSD.

Migrants and former refugees have unique challenges, as they are placed in communities without connections and, once established there, can find it hard to source accommodation for other family members who join them later. Refugee social service organisations have highlighted issues with former refugees who are resettled outside Tāmaki Makaurau; they can experience significant housing problems if they decide to self-settle in the Tāmaki Makaurau region to be closer to social and community supports.

Stats NZ reports that about 41,000 New Zealanders are homeless, and the situation is worsening. Mental health issues are also more prevalent: homeless people are 10 times more likely to experience depression than those who have homes.

More than half of the homeless population is under the age of 25. Some will have grown up in the foster care system, which ends at age 18, and some young people who leave home have nowhere else to go or few other options. Lifewise’s Youth Housing service provides safe housing and support for 16- to 24-year-olds who are homeless, are at risk of becoming homeless or have other serious housing needs.

It has been forecast that by 2030 New Zealand will have more than a million people aged over 65. Community housing providers have been working with the Government and councils to increase the supply of affordable housing and rental accommodation to meet the increasing estimated demand from older New Zealanders.

3.2 Key data – housing needs in Tāmaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau

Affordable housing

The Government and the private sector provide ‘affordable housing’3 through state and privately owned rental accommodation, rent-to-buy, shared equity, community and shared housing, and residential care provided by the state or NGOs.

New Zealand First announced in January 2020 that, according to Stats NZ, 37,010 residential building consents had been issued during 2019, an increase of 13% from 2018 and surpassing 37,000 for the first time since 1974. The increase in Tāmaki Makaurau was 16%. However, demand is increasingly outstripping supply.

Whatever housing solutions are developed, financing the cost of land, compliance, construction and services will be the primary challenge.

3The affordability criteria assume that no more than 30% of gross household income is spent on either paying rent or servicing a mortgage.

The intermediate housing market

The intermediate housing market is a growing subset of the private rental and housing sector; it covers households that cannot afford to buy houses or that are at risk of losing ownership4.

This is an important issue for Tāmaki Makaurau, where house prices and rental fees are the highest in the country – and for both Tāmaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau, as affordability is a barrier to the private rental and private ownership parts of the housing continuum. In turn, these issues affect the entire housing continuum, including providers, funders and home seekers.

Researchers have observed the ongoing decline in housing affordability for years, noting that, “if there is a single indicator that conveys the greatest amount of information on the overall performance of housing markets, it is the house price-to-income ratio” (Demographia, 2020, p6).

4The intermediate housing market is a collective term for private renter households with at least one person in paid employment that are unable to affordably purchase houses at the lower quartile house sale prices for their local authority areas, at standard bank lending conditions.

Key issues – data snapshot

Table 3 provides an overview of some key factors influencing the housing sector and housing need.

Table 3: Data snapshot of key housing issues and needs

Issue | Description |

| Declining home ownership | Between 1986 and 2013 the percentage of Māori living in owner-occupied dwellings fell in most local authority areas at a faster rate than the general population. It fell by 25% in South Auckland and West Auckland, and 28% in Northland (Stats NZ). In the same timeframe, the number of Pacific people living in owner-occupied dwellings dropped by 38%. In West and South Auckland the number dropped by 47% and 44% respectively (Stats NZ). |

| Rental costs | In November 2019 the average weekly rental cost in Northland was $400. In Tāmaki Makaurau it was $568 – the highest nationwide (Statista.com). |

| Accelerating housing consent numbers | In the financial year ending 30 June 2019, 10,364 dwelling consents were approved in Auckland and 1,289 in Te Tai Tokerau (Stats NZ). |

| Homelessness in Tāmaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau | According to Census data, Māori make up about one-third of the national homeless population (13,000). Homelessness grew by 2% per year between 2006 and 2013. The prevalence of homelessness, compared with that among Europeans, is 5:1 for Māori and 10:1 for Pacific. |

| Increasing population diversity and growth in the Tāmaki Makaurau region | According to data reported by Auckland Council in the 2018 Census, the Auckland region has the following population demographics: • 53.5% European. • 28.2% Asian. • 15.5% Pacific peoples (largely living in South Auckland). • 11.5% Māori. |

| Communities with housing needs – housing deprivation (health and housing) | The housing deprivation measure is the proportion of people in a district health board (DHB) region on low incomes living in overcrowded households and in rented dwellings. In 2017 Auckland DHB reported housing deprivation at 23% higher than the median rank for New Zealand. The figure for Counties Manukau DHB was 27.9% higher and for Waitemata DHB it was 2.1% higher. In the same year, reports from The University of Auckland and the Health Research Council ranked the following communities as having high housing deprivation: • Counties Manukau DHB: Māngere, Papakura, Pakuranga, Dannemora, Pukekohe, Tuakau. • Auckland DHB: Auckland CBD, western and eastern suburbs. • Waitematā DHB: Urban west Auckland and North Shore and Pāremoremo. • Northland DHB: Ahipara, Kaitāia, Karikari Peninsula, Kaikohe and 45 small areas in and around Whangārei. |

3.4. Regional housing issues and opportunities

This section presents key issues and opportunities for Te Tai Tokerau and Tāmaki Makaurau housing sectors; some also have national relevance.

4.1 Strengthening the community housing sector

Good results have been made possible through effective funding partnerships with community housing providers. In Tāmaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau, iwi, Māori authorities, community services groups and others are asking for help with housing finance, organisational capacity-building and compliance capabilities. They also build social connections in the communities they serve and wish to be better connected with each other.

4.2 Collaborative action to end homelessness

As in other countries, New Zealand’s biggest city has the most homeless people. Housing First providers in Tāmaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau are working together to deliver collective impact, but the model requires resourcing for backbone functions to be effective (for example organising, administration and convening). Despite an increasing will to work collaboratively, and strong evidence that this is an effective way to tackle complex social issues, funding is scarce for enabling collaboration in the community housing sector.

The Aotearoa New Zealand Homelessness Action Plan will provide a lever for councils and others in the housing system to work together, by supporting:

- Housing First and other prevention initiatives, such as financial capability education.

- Early intervention by mental health and social services to improve housing sustainability for people and families with complex needs.

4.3 Building more social housing

The community housing sector is seeking to increase the level of social housing, along with different types that offer integrated services and infrastructure for the people who live in them. This is a new model that offers greater potential for long-term success than large, stand-alone social housing developments, which international evidence shows often become slums.

4.4 Improving housing quality

Legislation has been enacted to improve the quality of housing and rental housing. In a scarce market, tenants are still afraid to challenge landlords about maintenance, neglect and other problems.

EECA’s insistence on auditing housing insulation and energy efficiency interventions for low-income households stands out at a time when housing quality may be compromised to manage the urgency of supply. Community housing provider development schemes included in this review emphasise the need for high-quality building standards.

4.5 Housing types to meet people’s needs

Implementing ‘universal design’ principles (catering for everyone, young and old, able and disabled) will enable housing diversity to align with best-practice standards. The community housing sector is leading the way by gathering and sharing valuable knowledge on managing design, construction and compliance processes. Te Matapihi is an independent voice for the Māori housing sector that was established in 2011. It brings together experts and researchers to co-ordinate knowledge and action, supports a biennial national Māori housing conference, and has close links with government and the community sector. It also provides access to high-quality information and resources for Māori organisations, including those building social housing.

Organisations such as Te Matapihi, Community Housing Aotearoa and the Housing Foundation are increasing their capabilities and advocacy for partnering with government, other investors and developers.

There is growing interest in community housing that involves cheap and quick builds – using prefabrication methods and constructing small (tiny) homes – that are acceptable forms of housing for many people.

For Māori the priority is design and affordability, so that iwi can re-establish kāinga and papakāinga at hapū level. To address the housing needs of Pacific, solutions are needed that accommodate large families without overcrowding, and the importance of financial assistance and support to manage and reduce debt. As for Māori, Pacific-led solutions will be key.

4.6 Regional and local action

This report has identified the localities where community housing need is most complex and urgent. Investments in transformative social change – such as The Southern Initiative (which supports a prosperous, resilient South Auckland) and the Western Initiative (which hopes to reduce youth unemployment in West Auckland) – provide opportunities to use concerted action to improve housing and other social conditions.

4.7 The Te Tai Tokerau housing landscape – key informant interviews

Between December 2019 and January 2020, the Centre for Social Impact conducted five interviews in Te Tai Tokerau. The interviews were a starting point for understanding the rapidly changing housing landscape in Te Tai Tokerau.

The interview participants were:

- Jade Kake – a Māori housing expert and advocate.

- Aroha Shelford, Uku Whare Papakāinga Development (earth building) and Ngāpuhi Social Services.

- Carol Peters – One Double Five Awhina Whare Community House, Whāngārei District Council and Northland DHB.

- Liz Makene and Sheryl Davis – Te Puni Kōkiri, Tai Tokerau (Whāngārei office).

- Rangimarie Price – Chief Executive at The Connective, former CEO of The Amokura Consortium.

Example issues emerging in Te Tai Tokerau

The interviews revealed a number of issues that are affecting housing sector responses in Te Tai Tokerau. They included:

- The need to address debt issues and increase legal and financial literacy, to enable whānau to increase their access to housing finance.

- The feasibility and infrastructure costs of developing housing on Māori land.

- The complexities involved in developing housing on Māori land – including the challenges associated with urban housing consent expectations being applied to papakāinga, and the barriers to using Māori land as collateral for loans.

The need for investment in regenerative housing solutions, including sustainable water and energy systems.

Example opportunities and innovations in Te Tai Tokerau

Innovative housing approaches and opportunities exist, and more are emerging in Te Tai Tokerau. For example:

- A group of mothers is planning a papakāinga housing development.

- A project involving Kamo High School students is building tiny homes as part of the Te Taitokerau Trades Academy.

- Effective new building approaches are being used, such as earthbag construction.

- BNZ is providing low-interest loans.

There are opportunities to strengthen papakāinga housing policies to address systemic issues with building consent processes.

Potential to increase sector engagement

The interviews made it clear that Te Tai Tokerau housing sector advocates and community providers value partnership-based funding models and seek authentic relationships with government and other NGOs, as well as funders.

All the interviewees said that this type of face-to-face engagement is a valued way of understanding the complexities of the housing sector in the North. They also stated that such engagement processes should be culturally appropriate, value participants’ insights and involve reciprocal and ongoing learning.

4 References, further reading and endnotes

5 Acknowledgements

Principal Author: Sue Zimmerman (Associate, Centre for Social Impact)

Co-authors: Kat Dawnier, Rachael Trotman (Associates, Centre for Social Impact)

Key Informant Interviewer: Kelly Kahukiwa (Associate, Centre for Social Impact)

Supporting Advice: Chloe Harwood and Shalini Pillai (Foundation North)

With thanks to the following people for their participation and invaluable insights:

Sheryl Davis, Jade Kake, Liz Makene, Carol Peters, Rangimarie Price and Aroha Shelford