1 Introduction

In 2020, CSI published a report The Housing Landscape in Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland) and Te Tai Tokerau (Northland).1 This work was commissioned by Foundation North to support their strategic considerations for investment in the housing sector.

Since that time, there have been significant wider contextual and policy developments that have warranted an update to the original housing sector report, including:

- The emergence of COVID-19 as a significant disruption to all aspects of life in Aotearoa, and internationally. The risks and impact of COVID-19 are greatest among vulnerable populations, including those in inadequate housing conditions.

- A notable emphasis of government budget and policies on prioritising Māori-led approaches and initiatives to reduce housing inequalities.

- Increasing advocacy for a human rights approach to be included in solving the housing crisis.

Foundation North commissioned CSI to update the 2020 report for the period January 2020 onwards, with a specific focus on Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland) and Te Tai Tokerau (Northland). This report provides a summative update of:

- housing sector data and sector influences

- legislation and policy changes.

The purpose of this updated report is to provide background and summary information on the impact and influence of housing as a key contributor to social wellbeing in Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland) and Te Tai Tokerau (Northland). Links to key government and other published documents are provided.

2 Housing Sector Update

Overview

In 2020 Statistics NZ published two reports on the state of housing in Aotearoa. They considered data from a range of official and government administrative statistics, to explore the extent to which New Zealand’s housing stock provides suitable, affordable, warm, safe, and secure shelter for its citizens. The Housing in Aotearoa: 20202 report focused on total population data; Te Pā Harakeke: Māori housing and wellbeing 20213 focused on Māori wellbeing data.

Summarising national data, the reports indicate areas of significant concern:

- 2018 Census data shows New Zealand’s homeownership rates are at their lowest since the 1950s.

- There have been greater falls for home ownership among Māori and Pacific peoples, and in the Auckland region.

- Pacific peoples and Māori are less likely to own their home or hold it in a family trust than other ethnic groups. They are also more likely, along with people with Asian, Middle Eastern, Latin American, or African (MELAA) ethnicity, to live in public housing.

- In New Zealand, house prices have been rising at a faster rate than wages over the past five years.

- Rates of severe housing deprivation are highest among young Pacific peoples and young Māori, while overall, severe housing deprivation prevalence rates for Pacific peoples and Māori are close to four and six times the Pakeha rate.

- Housing pressures are greatest among our most vulnerable citizens. One parent families, unemployed people and disabled people are more likely to experience poorer housing conditions.

- Māori and Pacific peoples are also more likely to experience poorer housing outcomes and higher rates of homelessness and crowding.

- In 2021, concerns about housing affordability and supply escalated regionally and nationally, particularly in Auckland. Rental affordability declined further in both the Auckland and Northland regions.

- Government interventions in the form of tightened Loan to Value ratios (LVRs) by the Reserve Bank and other measures were introduced. These measures were specifically designed to make the market fairer for first home buyers, and to reduce investors’ ability to offset interest paid on home loans against rental income.

- The average Auckland house price rose to $1.49 million (a 28 percent increase in 12 months) and 33 percent in the Far North.

- In October 2021 the National and Labour parties worked together to allow an Amendment to the Resource Management Act (RMA) Housing Supply Bill to progress urgently. This reduced resource consent requirements so that up to three homes of three storeys can be built on existing sites (with more intensification on request). It is anticipated this change will enable 105,000 extra new houses to be built in NZ within the next ten years.

3 Māori Housing and Wellbeing

Data about Māori housing and wellbeing4 demonstrates that:

- Housing is a core component of many aspects of Māori wellbeing, such as whānau health, acquisition, and use of te reo Māori, care of whenua and the environment, the ability to provide sustenance and hospitality for themselves and others, and many other aspects of wellbeing unique to Māori culture.

- Reductions in home ownership have not occurred uniformly across the population and declined at a faster rate for Māori than for Pakeha.

- Disparities in home ownership rates between Māori and Pakeha are evident for all age groups.

- Māori tamariki aged between 0 and 14 years were significantly less likely to live in an owner-occupied home than Pakeha children of the same age, with 43 percent of Māori children and 66 percent of Pakeha children living in a home owned by a member of their household.

- Māori whānau are more likely to live in rented homes, and are more likely to have moved frequently; 8.7 percent of Māori moved 5 or more times in the last 5 years, compared with 5 percent of Pakeha.

- Māori reported a higher rate of unaffordable housing (13 percent rated their housing affordability between 0-3) when compared with the Pakeha population (8.8 percent) and the total population (10 percent).

- Two in five Māori people lived in damp housing (40 percent), compared with two in five people of Pakeha ethnicity (21 percent), and 24 percent of the total population.

Additional information about initiatives and investments to support Māori housing aspirations and improve outcomes is provided in other sections of this report.

Te Matapihi

“Kia para ai te huarahi ki te ūkaipō, Forging Māori housing pathways”

Te Matapihi was established as a charitable trust in 2011 and launched as the national peak body for Māori housing at the watershed 2012 National Māori Housing Conference in Waitangi.

Te Matapihi’s Pūronga ā Tau/Annual Report for 2020-215 shows that in spite of unprecedented housing and social pressures experienced by Māori during COVID-19 alert restrictions, the Trust progressed its eight workstreams to improve housing outcomes for Māori, including: affordable home ownership, Community Housing Providers’ (CHPs) Affordable Rentals, Homelessness, Iwi, papakāinga Māori housing, cross sectoral relationships and governance and operations.

Te Matapihi is strongly connected with efforts to improve Māori housing outcomes across the system in Tamaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau.

MAIHI - Te Maihi o te Whare Māori

The Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (MHUD) launched Te Maihi o te Whare Māori – Māori and Iwi Housing Innovation Framework for Action (MAIHI)6, the National Māori Housing strategy, in October 2021. It is designed to drive a whole of system approach and provide strategic direction for the whole Māori housing system. MAIHI spans thirty years, (rather than electoral cycles) MAIHI is based on the articles (rather than the principles) of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Whai Kāinga Whai Oranga is a commitment of $730 million over four years to accelerate Māori-led housing solutions that are aligned with MAIHI.

Budget 2021 approved a combined investment of ($380m) and the Māori Infrastructure Fund ($350m) - the largest investment ever in Māori Housing.

Whai Kāinga Whai Oranga will support:

- Increasing organisational capability and capacity to deliver Māori-led housing solutions.

- Delivery of new or upgraded infrastructure to increase the supply of build ready land.

- Repairs for whanau Māori homes to improve housing quality in the immediate term.

- Housing projects that increase the supply of housing provided by Māori.

4 Public Housing

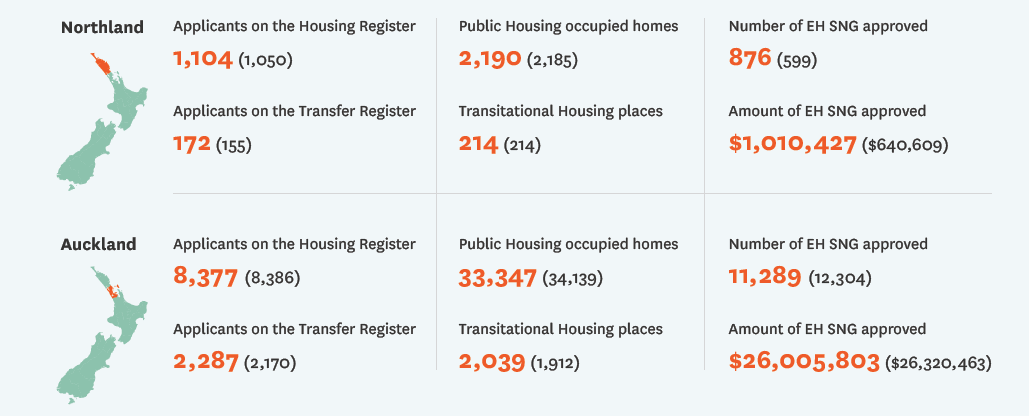

MHUD provides quarterly updates and regional information from MHUD, Ministry of Social Development and Kāinga Ora on the state of public housing and housing support. In December 2021 data reported from the quarter ending September 2021 included:

- Of 4,710 places available nationally for transitional housing, 214 were available in Northland and 2,039 were available in Auckland (delivered by 18 providers).

- Demand for public housing increased across almost all housing regions during the quarter compared with the previous year.

- Māngere-Otahuhu, Manurewa, Henderson-Massey and Maungakiekie-Tamaki were the localities with highest need.

The table below summarises information for the different types of government funded housing support provided. Data is provided relating to applicants on the housing register, public housing occupied homes and approved Emergency Housing Special Needs Grants (EH SNG).

Table 1: Public Housing Data

**Numbers in brackets denote previous quarter figure.

Source: MHUD (December 2021) – Public Housing Quarterly report7

The Ministry of Social Development publishes quarterly reports on benefit assistance trends, including some regional data. From these it appears that COVID-19 contributed to an increase in Special Needs Grants (SNGs) for food, emergency housing, electricity and gas, accommodation, and medical needs.

Data from government reports specific to Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland) and Te Tai Tokerau (Northland) has been summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: Key housing data for Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland) and Te Tai Tokerau (Northland)

| HOUSING COMPONENT | KEY FINDINGS FOR TĀMAKI MAKAURAU (AUCKLAND) AND TE TAI TOKERAU (NORTHLAND) |

| HOUSING TENURE AND TENURE SECURITY |

|

| HOUSING AFFORDABILITY |

|

| HOUSING HABITABILITY |

|

| HOUSING SUITABILITY, CROWDING AND HOMELESSNESS |

|

5 Housing as a Human Right

Nationally and internationally, there has been increased recognition of the inequities in access to adequate housing, and an increased focus on housing as a human rights issue. Local and international responses to this have included rights-focused policy guidelines, and the growth of social movements to support rights to housing and more effective models of investment to enable affordable housing. Examples are summarised below.

Te Kahu Tika Tangata/The Human Rights Commission

In August 2021 Te Kahu Tika Tangata/The Human Rights Commission (HRC) released initial guidelines The Framework Guidelines on the Right to a Decent Home in Aotearoa12 (see Appendix 1) along with an announcement that it will hold a national inquiry into housing.

The guidelines have been developed in partnership with the Iwi Chairs Forum, and with the support of Community Housing Aotearoa. The HRC’s aim is that the guidelines will provide a framework which can support and represent a first step towards enabling human rights to deepen and strengthen robust housing strategies, including those led by government in Aotearoa.

The HRC believes that, while the government has made progress on housing, the work across the public and private sectors lacks explicit recognition of the human right to a decent home. The guidelines are intended to address this problem and influence policy makers and other stakeholders in the public, private and community housing sectors by helping take human rights into account when designing and delivering housing services.

Since the launch of the framework in 2021 the HRC has developed a Measuring Progress tool13. The HRC will report against chosen measures on progress to enable more people in Aotearoa to live in a decent home in 2022.

The Shift: a housing movement

The Shift14 is a recent international movement to reclaim and realise the fundamental human right to housing – to move away from housing as a place to park excess capital, to housing as a place to live in dignity, to raise

families and participate in community. The movement is led by the previous UN Special Rapporteur on the right to

housing Leilani Farha, in partnership with United Cities Local Government and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

In 2019, Community Housing Aotearoa (CHA)15, in partnership with the Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities National Science Challenge and Māori Think Tank, launched The Shift Aotearoa. In 2021 CHA’s national conference focussed on The Shift and the human rights approach to housing.

The Shift reflects a growing recognition that a new approach to the housing crisis and homelessness is required and that effective responses require all parts of the housing system to be bought together to harness the strengths of government, iwi (tribes), communities, and business to fundamentally change conversations and ideas and decision-making.

CHA membership includes groups providing housing and support to many of New Zealand’s most vulnerable

people. These include the Construction Industry Council, Infrastructure New Zealand, the Property Council, and the New Zealand Green Building Council – and several larger local authorities. Te Matapihi (the peak body for Māori housing) works in partnership with CHA.

CHA has signed a multi-year memorandum of understanding to advance ‘evidence into practice’ towards building a well- functioning housing and urban system and supports the HRC Guidelines. CHA has also been successful in attracting substantial investment in The Shift from the JR McKenzie Trust’s Peter McKenzie Project.

Community Finance and the Aotearoa Pledge

Community Finance16 launched in 2019 and currently has advanced loans of more than $90m. The company was the Mindful Money 2021 winner of Best Impact Investment Fund award and is the Sustainable Business Awards Transforming New Zealand and Outstanding Collaboration prize winner for 2021.

Community Finance works with Community Housing Providers to provide finance and provide wholesale investors an impact investment opportunity.

Community Finance acts as an intermediary with loans secured and managed through securitisation to create a Community Bond. Community Finance typically charges 0.65% pa to manage both the investments, lending, and impact reporting.

Investors receive regular reports on the direct social impact of their investment, as well as a financial return of between 2% pa and 4% pa.

Launched in 2021, The Aotearoa Pledge is an impact finance collaboration led by Community Finance17, and involving investors from a wide range of sectors, who are

collaborating to address the housing crisis by raising $100m of commitment from wholesale investors to invest in new affordable housing.

The model uses community bonds to provide finance to leading Community Housing Providers such as the Salvation Army. The Community Bond is paying philanthropic and other investors up to 2.3% per annum.

The Aotearoa Pledge to has raised $71 million to date.

6 Legislation and Policy

Government legislation and policy

Two pieces of legislation enacted in 2019 and 2020 underpin the government’s implementation of associated policies

and investments to increase affordable housing supply in Aotearoa:

- 1. The Kāinga Ora–Homes and Communities Act 2019, and

- 2. The Urban Development Act 2020.

Table 3 includes updated summaries on the implementation of these and other associated legislation as well as

investment decisions announced and implemented in the period December 2019 to December 2021 to support the Government’s new housing directions outlined in Budgets 2020 and 2021. Housing policies continue to play a key part in government’s wider priorities for national wellbeing and COVID-19 recovery.

Table 3: Public policy and legislation changes with relevance and impact for the housing sector

| LEGISLATION | SUMMARY OF UPDATES SINCE DECEMBER 2019 |

| KĀINGA ORA HOMES AND COMMUNITIES ACT SEPTEMBER 2019 | This Act and the Urban Development Act oversee the partnership between the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and Kāinga Ora (KO). Changes implemented since 2019 include the following:

|

| THE URBAN DEVELOPMENT ACT 2020-2021 | This supports Kāinga Ora to improve social and economic performance of urban areas through complex development projects. New powers relate to funding, infrastructure, planning, consenting, and funding, including implementation of:

|

| HOUSING ACCELERATION FUND | A total of $3.8 billion was allocated in Budget 2021 for four years to increase housing nationwide. Minister Grant Robertson announced this funding would including “insulating 47,700 homes and putting $380 million towards raising Māori homeownership, which currently sits at just 30%. $131.8m will also go towards replacing the Resource Management Act, which is hoped to improve the delivery of new housing”. The funding will also support the government’s housing programmes through:

|

| THE RESIDENTIAL TENANCIES AMENDMENT ACT 200 | Enacted August 2020, this Act:

Phase 1: From 12 August 2020

Phase 2: From 11 February 2021

|

| THE AOTEAROA HOMELESSNESS ACTION PLAN 2020-2023 | This is a cross-government plan with a focus on prevention, supply, support, and system enablers. It aims to make homelessness ‘rare, brief and non-recurring. The Housing First programme continues to be government’s primary response to chronic homelessness. Government invested $197m to strengthen Housing First in 2019. The second six-monthly progress report24 (for the period September 2020 to February 2021 reported:

|

| THE CHILD POVERTY REDUCTION ACT 2018 (UPDATE) | This Act includes activities and investments that align with housing legislation and policy as well as Government priorities for Māori and Pacific peoples, child wellbeing and physical and mental wellbeing. Numbers of children who are homeless or living in precarious housing has increased in Auckland and Northland since 2019.25 Currently (2021) one in every four children in Aotearoa New Zealand lives in a low-income household where their family and whānau struggle to provide them with the basics needed to allow them to flourish. This number has more than doubled over the past 30 years.26 Government’s third child poverty report July 202127 reported:

|

| COVID-19 WELLBEING BUDGET 2021 – SECURING OUR RECOVERY | Budget 2021 initiatives funded from the COVID-19 Response and Recovery fund (CRFF). Government’s priorities for the current term identified in Budget 2021 are to:

|

| GOVERNMENT POLICY STATEMENT ON HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT (2021) | The GPS-HUD will provide a shared vision and direction across housing and urban development, to guide and inform the actions of all those who contribute.29 It will describe how Government and other parts of the housing and urban development system will work together to realise this vision. The GPS-HUD will shape future:

|

Auckland Council housing and policy

As a key stakeholder in the Auckland region, Auckland Council has continued to be active in the housing sector and has released a number of key strategic documents which outline its approach to housing and development. These are summarised below:

Auckland Plan 205030

- This outlines a proposed pattern of growth and development, focussing on delivery of a more compact city into the future in response to anticipated population and economic growth.

- The plan sets the council group’s strategic outlook and focuses on six key outcome areas. Homes and Places is one of the key direction areas. Its aim is that Aucklanders live in secure, healthy, and affordable homes, and have access to a range of inclusive public places.

- In the July 2021 Auckland Plan 2050 Progress Report, Council noted increasing numbers of dwelling consents and shifts to building of intensive housing as main factors. Increasing affordability continues to be challenging, and unachievable, especially for first home buyers.31

- Māori Identity and Wellbeing is another priority outcome area and includes papakainga and Māori housing. A Cultural Initiatives Fund ($1.2 million per annum) has been established to increase opportunities for papakainga development within Tāmaki Makaurau. The Māori Outcomes Fund grants total $17.6 million to date. Eight grants were made in 2020/21. Nine marae have grants for 2021/22.32

National Policy Statement on Urban Development NPS-UD

e In May 2021 Auckland Council endorsed policy approaches for implementing the government’s NPS-UD to guide further work to prepare for public engagement on changes to the Auckland Unitary Plan in August 2022.

e The NPS-UD aims to improve housing affordability. It directs councils to allow for more housing and businesses to be built – with greater height and density – in places close to jobs, community services and public transport and in response to market demand. Auckland Council’s Planning Committee agreed policy approaches that included walkable catchments around Auckland’s city centre, ten metropolitan centres and rapid transit stops. Auckland Council’s Chief Economist’s Unit issued its Economic Quarterly Report occasional paper in August 2021.33 The paper provides a useful review of the impact of policy and other influences (including COVID-19) on housing in the Auckland region. The Chief Economist notes that getting the NPS-UD and 3 Waters Reforms implemented effectively are crucial issues for the region’s sustainable development.

Other council/government policy- led housing initiatives

- Auckland Council is working with Kāinga Ora through the Auckland Housing and Urban Growth joint programme to ensure adequate provision of social and community infrastructure to meet the needs of new communities result from government housing developments. Funding and finance infrastructure to accommodate planned growth is one of Auckland biggest challenges (to accelerating housing provision).

- Innovative housing projects completed or underway that reflect new partnerships and approaches include Henderson Green where 38 townhouse and 78 apartments are being constructed through a public private partnership using Council land in West Auckland.34 In Point England and Onehunga a partnership between a Kiwisaver provider (Simplicity) and a building developer (NZ Living) intend to build 192 high quality build-to-rent apartment homes of various sizes.35

7 Concluding comments

Access to affordable and appropriate housing is a key lever in achieving positive wellbeing outcomes for whānau and communities across Auckland and Northland. However, decades of disinvestment in public housing and national policy measures to enable equitable access to housing that meets people’s need has become increasingly challenging, particularly in the Auckland region.

The data in this report identifies the impact of recent government, Māori, and collaborative leadership to accelerate the urgent systems change action and effective investment to address the key issues, including:

- The acceleration of wider impacts of the housing crisis as appropriate and affordable housing becoming increasingly difficult to access across Auckland and Northland.

- The impacts of the housing crisis are disproportionately experienced by whānau who are already vulnerable due to existing inequalities, including Māori and Pasifika, low income whānau, rangatahi and those living with disabilities.

- COVID-19 and alert restrictions have heightened impacts of existing inequalities on vulnerable families and whānau. Poor housing conditions have affected the spread and impact of COVID-19, particularly among vulnerable people in transitional and crowded housing.36

- There is increasing advocacy for a stronger policy focus on housing as a human rights issue. In Aotearoa there are a growing number of stakeholders working together for comprehensive systems change, with an increased focus on human rights approaches to property investmen that challenges the currently dominant view of housing as an effective, as well as lucrative form of personal and corporate investment. Monitoring and reporting systems have been established to measure the impact of legislative and other changes on improved housing outcomes.

- A wide range of legislation supporting improved housing sector outcomes has been implemented in 2020-2021, with a strong focus on improving access to affordable housing for those in greatest need, supporting Māori and Iwi Housing Innovation partnerships and setting standards for adequate rental housing. While being supportive of change and impact, it is unclear whether these approaches will be sufficient to have an impact on changing the current trajectory of the housing sector in Auckland and Northland.

- In 2021 Auckland and Northland Councils took significant steps to accelerate new housing supply, facilitated by government legislation. This is reflected in record numbers of building consents issued that reflect the changing form of urban environments (increasing intensification and housing types).

- New investment partnerships are progressing innovative projects, including social housing and build to rent and government efforts to make the market fairer for first home buyers. (In October 2021 the median house price in Auckland was $1.25 million (19 percent higher than the previous year).

- National and regional efforts are underway to address housing, not only as an equity issue but for its contribution to climate change goals.

- Legislative and policy changes are being made to support aspirations for Māori housing outcome solutions to be led by Māori.

Appendix 1: Guidelines on the Right to a Decent Home in Aotearoa (2021)

Source: Human Rights Commission. The Framework Guidelines on the Right to a Decent Home in Aotearoa, August 202137

| GUIDELINE 1 | IN AOTEAROA, THE HOUSING SYSTEM MUST BE EXPLICITLY BASED ON VALUES (AS OUTLINED IN GUIDELINE 10), THE INTERNATIONAL RIGHT TO A DECENT HOME, TE TIRITI O WAITANGI AND EVIDENCE OF WHAT WORKS. |

| GUIDELINE 2 | Grounded on Te Tiriti, the international right to a decent home is more than a right to shelter, bricks, mortar, or a house. It is the human right to a warm, dry, safe, secure, affordable, accessible, healthy, decent home, as understood by Te Ao Māori. By way of shorthand, these Guidelines refer to the ‘right to a decent home’. |

| GUIDELINE 3 | Agreed by successive New Zealand governments, the right to a decent home is ethically compelling and binding on New Zealand in international law. This human right does not favour one socio- economic system, but it requires that the selected system is consistent with human rights and democratic principles, enhances enjoyment of the right to a decent home, and honours Te Tiriti. |

| GUIDELINE 4 | The international right to a decent home must be located and applied within the unique historical, demographic, economic, social, cultural, environmental, and legal context of Aotearoa. |

| GUIDELINE 5 | Te Tiriti and the right to a decent home not only place obligations on central and local government, but they also place responsibilities on others, including the private sector, landlords, property managers, service-providers, and tenants. |

| GUIDELINE 6 | Central and local government have a shared responsibility to do everything in their power to deliver the right to a decent home, grounded on Te Tiriti, for everyone in Aotearoa. |

| GUIDELINE 7 | The right to a decent home grounded on Te Tiriti empowers individuals, hapū, iwi and communities in their engagement with central and local government; helps policy makers strengthen their housing initiatives; and helps ensure that housing commitments are honoured. |

| GUIDELINE 8 | The right to a decent home grounded on Te Tiriti is a framework on which everyone who is committed to tackling the housing crisis can build respectful relationships, multiple partnerships, and effective collaboration. |

| GUIDELINE 9 | The right to a decent home grounded on Te Tiriti requires acknowledging and addressing the impacts of colonisation, systematic dispossession of Māori from their land, and destruction of their traditional ways of living, including communal land ownership. Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples have a critically important role to play in advancing the right to a decent home in Aotearoa. |

| GUIDELINE 10 | Values, such as whanaungatanga (kinship), kaitiakitanga (stewardship), manaakitanga (respect), dignity, decency, fairness, equality, freedom, wellbeing, safety, autonomy, participation, partnership, community, and responsibility, are embodied in the right to a decent home. These values, and the right to a decent home grounded on Te Tiriti, must lie at the centre of all housing-related initiatives in Aotearoa. |

| GUIDELINE 11 | All housing initiatives must comply with the seven UN ‘decency’ housing principles read with Te Tiriti o Waitangi: habitable; affordable; accessible for everyone; services, facilities, and infrastructure; location; respect for cultural diversity; and security of tenure. If homes and housing initiatives do not comply with a ‘decency’ principle they are not complying with the right to a decent home, unless it can be shown that all reasonable steps have been taken to comply with the principle (see section 4). |

| GUIDELINE 12 | Because the right to a decent home includes freedoms, all restrictive housing laws, regulations, rules, and practices must be fair, reasonable, proportionate, and culturally appropriate. |

| GUIDELINE 13 | A decent home must be accessible to everyone without discrimination on prohibited grounds, such as disability, ethnicity, religion, age, gender, or sexual orientation. Effective measures, designed to address the unfair disadvantage experienced by some individuals and communities, are required. |

| GUIDELINE 14 | In accordance with international human rights treaties and declarations, ensure all individuals and communities have the opportunity for active and informed participation on housing issues that affect them. Additionally, Te Tiriti requires government to work in partnership, and share decision-making, with its Tiriti partners. |

| GUIDELINE 15 | Central and local government must have an overarching housing strategy. The housing strategy must be based on human rights and Te Tiriti. Te Tiriti and human rights-based housing strategy must have the right to a decent home at its centre. |

| GUIDELINE 16 | All housing initiatives must be subject to constructive accountability i.e., initiatives must be assessed against the human right to a decent home grounded on Te Tiriti. Constructive accountability must be both effective and accessible to those in need. |

| GUIDELINE 17 | If the government’s development and aid programme include housing initiatives, it has a responsibility to ensure the initiatives are consistent with the right to a decent home and, where the recipient country has indigenous peoples, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. |

| GUIDELINE 18 | The right to a decent home grounded on Te Tiriti places measurable obligations on central and local government. Full implementation of the right to a decent home may be progressively realised over time. But central and local government must take deliberate, concrete, and targeted steps towards realisation of the right to a decent home. Government has a specific and continuing obligation to move as expeditiously and effectively as possible towards the human right’s full implementation. Progress (or otherwise) must be tracked by suitable indicators and benchmarks. When prioritising in relation to the right to a decent home, certain conditions apply, such as consideration of colonisation and its continuing impacts, Te Tiriti and the most disadvantaged individuals and communities, including those living in poverty. |

| GUIDELINE 19 | Central and local government have obligations arising from the right to a decent home grounded on Te Tiriti. The obligation to respect places a responsibility on government to refrain from interfering directly or indirectly with the enjoyment of the right to a decent home grounded on Te Tiriti. The obligation to protect means that government must prevent third parties, such as private landlords, from interfering with the enjoyment of the right to a decent home grounded on Te Tiriti. The obligation to fulfil requires government to adopt all appropriate measures, including legislative, administrative, and budgetary, to ensure the full realisation of the right to a decent home grounded on Te Tiriti. Breaches of these obligations may give rise to violations of the right to a decent home grounded on Te Tiriti. |

| GUIDELINE 20 | The private sector has obligations arising from the right to a decent home. Further attention should be given to (a) clarifying the responsibilities of the private sector in relation to the right to a decent home grounded on Te Tiriti and (b) identifying suitable constructive accountability arrangements in relation to these private sector responsibilities. |

| GUIDELINE 21 | These Guidelines provide a framework on which we can all build. All stakeholders are encouraged to develop and apply the framework with a view to enhancing the right to a decent home grounded on Te Tiriti for everyone in Aotearoa. |

References

- 1 centreforsocialimpact.org.nz/knowledge…

- 2 stats.govt.nz/reports/housing-in-aotea…

- 3 stats.govt.nz/reports/te-pa-harakeke-M…

- 4 stats.govt.nz/reports/te-pa-harakeke-M…

- 5 tematapihi.org.nz/resources/2021/11/21…

- 6 hud.govt.nz/maihi-and-maori-housing/ma…

- 7 hud.govt.nz/assets/News-and-Resources/…

- 8 Statistics NZ stats.govt.nz/informat…

- 9 interest.co.nz/property/house-price-in…

- 10 thewarehouse.co.nz/thewarmhouse

- 11 aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects…

- 12 hrc.co.nz/files/9416/2855/9704/HRC_Hou…

- 13 hrc.co.nz/our-work/right-decent-home/m…

- 14 make-the-shift.org

- 15 CHA is the peak body for the community housing sec…

- 16 communityfinance.co.nz

- 17 communityfinance.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/…

- 18 hud.govt.nz/assets/Community-and-Publi…

- 19 hud.govt.nz/assets/Community-and-Publi…

- 20 hud.govt.nz/assets/News-and-Resources/…

- 21 veros.co.nz/urban-development-in-2021-…

- 22 kaingaora.govt.nz/assets/Developments-and-…

- 23 20 homes in Kamo (2020) and 37 in Maunu (2021). 21…

- 24 hud.govt.nz/assets/Community-and-Publi…

- 25 nzherald.co.nz/nz/number-of-children-l…

- 26 theshiftaotearoa.org/resources

- 27 childyouthwellbeing.govt.nz/sites/default/…

- 28 cpag.org.nz/assets/CPAG_2021_1st_year_…

- 29 hud.govt.nz/urban-development/governme…

- 30 aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects…

- 31 aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects…

- 32 aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/about-auckland…

- 33 aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/about-auckland…

- 34 ourauckland.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/news/2…

- 35 simplicity.kiwi/learn/updates/simplicity-l…

- 36 nzherald.co.nz/nz/covid-19-delta-outbr…

- 37 hrc.co.nz/files/7416/2784/4778/Framewo…