1 Executive Summary

This report is based on an earlier report developed for Foundation North in early 2022. It intends to make available knowledge to the wider philanthropic and non-profit sectors that supports system-level outcomes in relation to food/kai.

Food security is a symptom of inequity

In Aotearoa New Zealand, an estimated 10% of the population is food insecure, yet we produce and import enough food to feed 30 million people each year. The cost of healthy food is high and food waste in this country is extreme.

Food security is an equity issue, with research highlighting the link between food insecurity and income inadequacy, particularly for Māori, Pacific peoples, and households made up of children, young people and women.

Wider systemic issues perpetuate this inequity, including the high cost of living (particularly groceries and housing), unsustainable business practices such as food overproduction and food waste, fragmented policy and regulatory environments that favour commercial interests and enable the current supermarket duopoly, and singular responses that prioritise meeting immediate needs over systems change.

Government strategy, policy and legislation is fragmented and focused on narrow issues – such as food safety, health or environmental issues. There is no ministry with overall responsibility for the food system, no co-ordinated cross-ministerial activity, and no national plan – although development of a national strategy is being led by The Aotearoa Circle.

Food security and food sovereignty

Food security is achieved when people have consistent and secure access to affordable, nutritious, safe and culturally acceptable food. The term ‘food sovereignty’ refers to a food system in which the people who produce, distribute, and consume food also control the approach to and means of food production and distribution. Māori food sovereignty “empowers whānau and hapū driven food production” (Hutchings, 2015).

Reviewing the landscape of responses to the current inadequate food system shows diverse examples ranging from meeting immediate food insecurity via community food organisations, to collaborative food networks and social purpose businesses driving Māori food sovereignty and wellbeing (see Appendix 1).

Opportunities for system-level impact

Opportunities for philanthropy and the non-profit sectors to support transformational change in relation to food systems in Aotearoa centre on four spaces:

Focus | What this could look |

(1) Addressing income inadequacy and inequitable access to good food |

|

| (2) Enabling Māori food sovereignty |

|

| (3) Supporting Pacific food security |

|

| (4) Supporting regenerative, inclusive and resilient local food system initiatives |

|

2 Introduction

Across its community engagement and funding programmes in 2020 and 2021, Foundation North (FN) identified a growth in funding applications responding to challenges related to kai/food. Existing inequalities around access to affordable, nutritious and sustainable kai were exacerbated by COVID-19. In addition to funding crisis response, FN was also interested in understanding how to best contribute to systemic change in relation to kai, given its strategic focus areas of Increased Equity, Social Inclusion and Regenerative Environment.

The Centre for Social Impact (CSI) developed a report to inform FN on how it might support system-level outcomes in relation to kai. This report is derived from that original report to share knowledge with the wider philanthropic and non-profit sector. This report explores:

- Current trends in addressing kai access, affordability and sustainability

- Key systems-change levers

- Opportunities to drive change through funding and non-funding roles.

This report was informed by:

- A desk-top review of relevant literature and reports

- Key informant interviews held with nine stakeholders (see Appendix 2) engaged with food systems change work as investors, researchers and with involvement in current initiatives in Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland) and Te Tai Tokerau (Northland).

3 Food insecurity

3.1. Definitions

Food systems are described by the OECD (n.d.) as “all the elements and activities related to producing and consuming food, and their effects, including economic, health, and environmental outcomes”.

There are three global challenges affecting food systems:

- Ensuring food security for growing populations experiencing inequities of income, health and wellbeing.

- Supporting livelihoods of food producers and others employed across the food chain.

- Addressing the environmental impacts of food production and consumption.

The health and socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 have exacerbated these challenges, with research identifying the need for food systems to be part of efforts to grow community resilience, inclusion and sustainability (ibid).

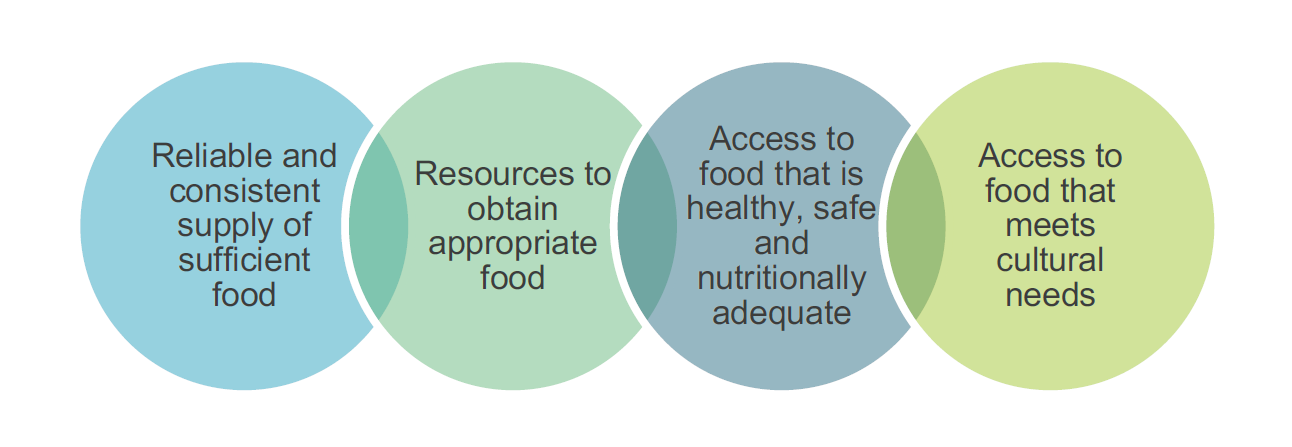

Food security as defined by the United Nations’ Committee on World Food Security, means that “all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life” (UN, n.d.). In the Aotearoa New Zealand context, food security is further defined to include “acceptable foods that meet cultural needs in a socially acceptable way” (MSD, n.d.). The diagram below outlines the key components of food security.

Globally the prevalence of moderate to high food insecurity is estimated to have risen more in 2020 than in the previous five years combined (UN, 2021). Food insecurity can be temporary (less than 16 weeks), caused by sudden shocks, such as loss of income or health issues; or ongoing (Kore Hiakai, n.d.)

Food sovereignty is a term developed at the 1996 World Food Summit by La Via Campesina (2021), to mean “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems. It puts the aspirations and needs of those who produce, distribute and consume food at the heart of food systems and policies rather than the demands of markets and corporations”.

The concept of food sovereignty goes beyond food security by explicitly recognising that food is more than a commodity. The importance of Indigenous knowledge, community self-determination, localised systems, sustainable livelihoods and regenerative ecosystems are acknowledged as being integral to a sustainable food system (Food Secure Canada, n.d.).

In Aotearoa, Māori food sovereignty “puts Māori who produce, distribute and consume food – rather than the demands of global markets, free trade agreements and corporations – at the heart of food systems and policies… Māori food sovereignty empowers whānau and hapū driven food production, distribution and consumption based on environmental, social, cultural and economic sustainability” (Hutchings, 2015).

Māori food sovereignty recognises the rights of Māori to “eat from the lands and waterways of our tūpuna (ancestors)…. [to] restore our relationship to the natural environment by producing our own food…[and] to nurture hauora (wellbeing) at the same time as reconnecting us with the energies of Papatūānuku and Ranginui” (ibid).

3.2. Drivers of food insecurity

“Ultimately, inadequate income is what causes someone to experience food insecurity. But increasing incomes alone will not solve Aotearoa’s food inequalities. This is a ‘wicked’ problem – it’s complex, interconnected with other social issues, and is hard to define and measure. Ending food poverty in New Zealand will require a collaborative approach – which makes use of numerous, innovative, interconnected, cross-sector initiatives” (Kore Hiakai, n.d.)

Aotearoa produces enough food each year to feed 20 million people and imports enough food to feed 10 million people (CPAG, 2019); and yet an estimated 10% of the population is food insecure (ACM, 2019). The level of food waste in Aotearoa is staggering.

Food insecurity is symptomatic of entrenched inequalities that drive poverty, low income and exclusion. Research “indicates a strong relationship between food insecurity and low income. When disposable income is limited, quality and quantity of food is often one of the first items that is compromised” (DPMC, 2021, p.14). Other systemic issues reinforce income inequity, including for example:

- The escalating cost of housing and other essentials in Aotearoa, which leaves little for lowincome

families to spend on food (i.e. a too high cost of living relative to wages and benefits). - Inequitable access to education and income, driven by factors that include racism, discrimination and colonisation (Dawnier, K. and Trotman, R., 2020).

A range of other intersecting systemic issues play a role in driving food insecurity, including (The Southern Initiative [TSI], 2020; Commerce Commission, 2021):

- Loss of productive land, waste, unsustainable business practices and commercial imperatives (e.g., supermarket duopoly, high profit margins, competition for wholesale purchasing) driving up the cost of food.

- A policy and regulatory environment that favours commercial interests over community wellbeing.

- Fragmented responses to addressing issues within the current food system.

3.3. Who experiences food insecurity in Aotearoa?

In 2019, the Auckland City Mission (ACM) published research based on a survey of 650 foodbank users, finding that food insecurity is disproportionately experienced by women and children, and by Māori and Pacific whānau and aiga. More than 40% of those survey had experienced chronic food insecurity of two years or more. In 2019/20, 20% of households with 0–15 year olds reported food running out sometimes or often – involving around 160,000 children. This increased to 30% for tamariki Māori and 46% for Pacific children. Children living in socio-economic deprivation index deciles 9–10 (most deprived) experienced higher rates of food insecurity (40%) (DPMC, 2021; Child Poverty Action Group, 2019). Other factors that mean children are more likely to experience food insecurity include when they (CPAG, 2019):

- Live in a household with low income.

- Live in a household supported by a government benefit.

- Live in rented accommodation.

- Live with two or more other children.

The Ministry for Social Development administers hardship assistance including Special Needs Grants (SNGs) for food. SNGs have trended down since December 2020 – following growth after the March 2020 Covid-19 lockdown. There was a similar spike in August 2021 following lockdown (MSD, 2021). Over half of the Special Needs Grants for food distributed in October 2021 went to Māori (52%).

In the year to July 2021, the Auckland City Mission alone distributed 48,679 food parcels to people based in Auckland, in addition to meals provided through its Haeata Community Centre

The impacts of food insecurity

Evidence shows that food insecurity contributes to a range of life course impacts, including (DPMC, 2021, p.14; ACM, 2014; ACM, 2019):

- Malnutrition and obesity due to cheaper, energy dense foods.

- Child health, development and behavioural concerns.

- Poor youth mental health.

- Poor educational outcomes.

- Unmet primary health needs.

- Family and relationship stress.

- Parent emotional stress and mental health associated with finding food and hiding financial strain from children.

- Shame and social isolation.

- Health-related social problems including substance use (CPAG, 2019; Tanielu, R., 2021).

3.4. Government policy and strategy

“There are 31 primary agencies in government with a role in the food system” (Hancock, F, 2021), yet there is no dedicated Ministerial department responsible for ensuring that “New Zealanders have access to a food supply that meets the food-based dietary guidelines of the Ministry of Health” (CPAG, 2019, part 1, p.6); and no national food strategy (though one is in progress). Following calls to action from community organisations and advocates, there is some progress towards a national food roadmap under the Mana Kai Initiative (see further below) with KPMG appointed as secretariat to facilitate its development by public and private sector think tank The Aotearoa Circle (2020).

Below are examples of policy, funding and other responses to food system issues across government:

- The Ministry for Social Development administers hardship assistance including Special Needs Grants for food (see above); and through its Covid Recovery Budget will have invested $32 million over two years (up to June 2022) to provide support for foodbanks, food rescue and other community organisations who are distributing food to vulnerable people and whānau and building community-led solutions for food security (Tanielu, R., 2021)

- The Ministry for Primary Industries has a Food Safety Strategy; whilst its overall strategy includes a focus on increasing food value, more sustainable food growing, fishery and land use practices, preservation of biodiversity and partnerships with Iwi and Māori (2019).

- The Ministry for the Environment (2021) is currently undertaking public consultation as part of its waste legislation and strategy review. Discussion documents for this review include consideration of reducing emissions from food waste and food production systems, extending food rescue programmes, expanding food waste education.

- The Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy (DPMC, 2019) includes a focus on ensuring children have regular access to nutritious food.

- The Ministry of Education (MoE) provides the Ka Ora, Ka Ako healthy school lunches programme, which aims to “reduce food insecurity by providing access to a nutritious lunch in school every day. By December 2021, over 47 million lunches have been served in 921 schools to over 211,000 learners” (MoE, 2021).

4 Opportunities for system-level change

“There is an urgent need for developing local food systems that are regenerative, inclusive and resilient, understanding that food can play a critical role in driving systemic change and if produced, delivered, selected and consumed in a sustainable manner, it can improve individual and collective wellbeing, foster multiculturalism and social cohesiveness, build climate and community resilience, preserve and restore the natural environment, create jobs and regenerate communities” (TSI, 2020).

“Food banks are a failed model that continue the duopoly of the supermarkets. We need something fairer and more mana enhancing” (Participant quote).

The extent of food insecurity in Aotearoa highlights the ongoing need for initiatives that meet the immediate needs of feeding whānau. Foodbanks, pātaka kai, food rescue organisations and community kitchens will continue to require resources to meet this need, in the absence of the root causes of food insecurity being addressed.

A strategic opportunity in this space is to support community food organisations to build their capacity and capability to connect, to collaborate and operate as local, regional and national networks, and to more effectively meet the nutritional needs of whānau and cultural needs of Māori and Pacific peoples.

Opportunities for transformational change in relation to food insecurity centre on four spaces:

- Addressing income inadequacy and unequal access to good food

- Enabling Māori food sovereignty

- Supporting Pacific food security

- Investing in initiatives that disrupt the current food system and support regenerative, inclusive and resilient local food systems.

Each of these four opportunities for driving systems change are explored below, with suggestions made on the potential role(s) for the philanthropy and non-profit sectors in each space (CPAG, 2019; ACM, 2019; Blakely, T. et al, 2020; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN, 2021; King, P. et al., 2010; Kore Hiakai, n.d.; Moeke-Pickering et al., 2015; Tanielu, R., 2021; Tonumaipe’a, D., et al, 2021; Weave, 2021; World Economic Forum, 2017; key informant interviews).

Appendix 1 provides examples of initiatives that meet immediate needs as well as initiatives that seek transformational change across the four spaces highlighted.

Address inequity and income inadequacy

“Those most vulnerable in the food system are women, Māori, Pasifika. We expect more Covid-like shocks that will exacerbate these existing inequalities” (Participant quote).

“When it comes to solutions we need to be clear on what is the problem we are trying to solve – it is about inequity… If we believe in solving the equity issue, solutions have to be Māori-led. We have to privilege Māori solutions, the voice of Māori. It is boring to keep saying it, but we have to do it. If we accept the underlying cause of inequity is colonisation then [funders] have to do our part in the decolonising process – step one is to understand our role in it; step two is to privilege Māori solutions and step three is to get out the way” (Participant quote).

Food insecurity is a symptom of structural inequalities that have developed over generations, with colonisation a driving force. Shifting the conditions that create food insecurity must therefore focus on:

- Improving income adequacy by increasing government benefit levels, providing a living wage and supporting whānau to lift household income, for example

- Addressing the impacts of colonisation, enabling tino rangatiratanga and mana motuhake.

This could involve:

- Supporting in initiatives that promote income adequacy for communities disproportionately experiencing food insecurity in the region Māori, Pacific peoples, households made up of children, young people and women)

- Support other areas that impact income adequacy e.g. affordable housing

- Supporting advocacy efforts related to income adequacy e.g. living wage, raising benefit levels, affordable housing, lowering the cost of living

- Prioritising Māori and Pacific food security and sovereignty (see further below).

4.1. Enable Māori food sovereignty

“We have based all of the food system on capitalism, and it’s an after effect of colonisation. It is not an Indigenous model” (Participant quote).

“Food parcels are a crisis response and in no way move people to food security and sovereignty. We want a food system for all people to access culturally appropriate and meaningful food – whether from a supermarket or growing it themselves” (Participant quote).

“Māori food sovereignty is re-centring “Māori healthy kai” as a vital part of the tikanga, culture and whenua. It encourages Māori communities to revive traditional kai access and use, and become more knowledgeable about nutrition and health” (Moeke-Pickering et al., 2015, p.38)

“We want to see our communities having an active and reciprocal relationship with Tangaroa; to the sea being the source of our wellbeing. We are very focused on reconnecting with that whakapapa that we have with the oceans, not just as a source of food but as a source of

prosperity” (Participant quote).

The food security inequities experienced by Māori and Pacific peoples mean that supporting Māori and Pacific food sovereignty is imperative. For Māori, this means having a reciprocal relationship with the land and sea, being in control of the kai that nourishes them and having self-sufficient access to nutritious food that supports physical, cultural, social and economic wellbeing.

Food sovereignty can be enabled through protecting, reconnecting and re-establishing:

- active engagement with: whenua, moana, māra kai, hunting and gathering

- mātauranga Māori, knowledge and cultural practices related to growing, preparing and consuming kai

- traditional ways of farming/producing food

- access to traditional Māori foods and seeds.

At a national level, there is significant opportunity to enable food sovereignty and create systemic change through developing the Māori food economy, which supports access to and control of affordable, nutritious and culturally appropriate foods; as well as offering value (revenue and jobs) across the supply chain that benefits Māori whānau and communities. Impact investment opportunities in this space are significant and include:

- research and development around commercialising new food products and technologies, an example identified by participants was the use of seaweed as a source of high value bioactive ingredients, as well as food

- development and scaling of Māori-led food companies and products with commercial and community impacts.

Partnerships with small tertiary providers are an opportunity to support education initiatives that build whānau knowledge about how to thrive through food, and to re-establish traditional cultural knowledge and practices around food. This can also act as a gateway for Māori to engage in educational pathways with potential to lead to high value and resilient jobs within the food system e.g., data science, engineering.

“Once people are learning about things that they connect with at a wairua level, that opens up the door to continue that education pursuit… We don’t have Māori marine engineers, executive representatives, STEM heavy roles in that economy. We want to build a knowledge ecosystem within those high demand, high resilience skill sets” (Participant quote).

Supporting Māori food sovereignty could look like:

- Supporting Iwi and Māori-led initiatives that protect and restore Māori control over kai

- Supporting grassroots organisations/projects engaged in kai sovereignty work to connect, network and grow their capacity

- Using impact investment to help build the Māori food economy, supporting R&D and growing the commercial capacity of Māori-led regenerative farming and aquaculture

- Partnering with education providers, wānanga and marae to invest in offering education opportunities (e.g. micro-credentials) that build whānau knowledge around kai and create education pathways towards resilient jobs in the food sector.

4.2. Increase Pacific food security and access to good food

“We are empowering community leaders to build connections to families and can work on the food security issues that each of those families has… The leadership of the Kai Collective are all Māori and Pasifika, so we lean heavily into Indigenous ways and practices… We are shifting away from a capitalist model of food distribution and creating a food network that creates security and empowerment. One of our groups is really excited about making a taro plantation at the back of one of our community centres; some people love fishing” (Participant quote)

As with the Māori food sovereignty imperative noted above, the food security inequities experienced by Pacific peoples mean that supporting Pacific food security and access to good food is also critical. For Pacific peoples, this means:

- growing and preparing traditional foods

- a more collective system of food distribution that centres on: the importance of aiga, community relationships and connectedness.

Supporting Pacific food security could look like: - Investing in initiatives that raise Pacific household income adequacy

- Investing in Pacific-led initiatives that enable access to healthy, nutritious and culturally relevant foods, particularly targeting areas of South Auckland where Pacific populations are high and access to good food is limited

- Investing in Pacific-led initiatives that support collective systems of food production and distribution e.g. Pacific food hubs

4.3. Invest in initiatives that disrupt the current system and support regenerative, inclusive and resilient local food systems

“The redesign of the system won’t happen on Lambton Quay. There is systematic inertia in central government, so we need to mobilise impact driven capital towards shining a light on innovative projects” (Participant quote).

“We don’t have a single food framework across any ministry. We don’t have one nationally; we do not have a single council that has one. There is nothing that guides a response to food insecurity or that walks towards food sovereignty… The Government is so focused on our export system – there is no deeper lens on the food system in our communities. They are not taking [food insecurity] seriously, they are doing parcels and are not doing any kind of innovation or alternative ways [of developing the food

system]” (Participant quote).

“There is so much happening in Tai Tokerau – whānau and community-led activity – one of the roles [to] play is in connecting this work” (Participant quote).

The Healthy Families team within Auckland Council’s Southern Initiative has developed the Good Food Road Map, which describes a more sustainable food system where good food is affordable, available, accessible, locally grown, culturally diverse, and where there is a stable, community-led and sustainable supply. This model advocates for local food systems that nurture mana-enhancing community participation.

Research identifies a number of opportunities for disruption of the current system – including policy/legislative change and food production practices:

- A national food strategy (as noted), with a shared vision to coordinate transformative action, supported by cross-ministerial action that links food, agriculture, health, culture and environment

- Lowering the cost of nutritious food through subsidies and taxation of fruit and vegetables and junk food respectively

- Incentivising local food production and local, short supply chains

- Challenging the existing supermarket duopoly, which the Commerce Commission (2021) found is driving up prices, to lower the cost of food and increase consumer choice, achievable through legislative levers and investment in alternative wholesale suppliers and retailers

- Legislative action to reduce food waste to landfill, decreasing overproduction and environmental pressure on productive land

- Reshaping existing community initiatives and infrastructure (e.g., community gardens) into a more connected food network

- Focusing on areas of high socio-economic deprivation to create food hubs or ‘food havens’ – “a space (Vā) or place (papakāinga) where people have high availability of healthy food that is culturally accessible, convenient, affordable and desirable” (Tonumaipe’a et al., 2021)

- Supporting regenerative agriculture and climate resilience across the food system

- Community food co-operatives / producer clusters.

This could look like:

- Investing in community-led food systems that are clearly linked to building community resilience and food sovereignty, including scaling and replicating existing local food models (e.g. Food Hubs) and on connecting solutions, sharing Intellectual Property (IP) and building food networks/ecosystems

- Advocacy (direct to government, or by investing in community voices driving food sovereignty) – including a national food strategy representative of community aspirations and one ministry charged with delivering on this strategy

- Impact investment into future food companies that offer social, environmental and cultural benefits, particularly opportunities within the Māori food economy (as above).

5 References

6 Appendix 1: Current landscape – examples of responses

The table below provides information about a range of example responses to advancing food security and food sovereignty. This is not a definitive map but provides an overview of initiatives/organisations that are working to tackle different aspects of food insecurity and food system change e.g. meeting immediate whānau needs, increasing access to affordable and nutritious food, reducing waste (climate action and food system resilience), food sovereignty and local food systems.

Response | Food system focus | Summary |

| Community food organisations | Meeting immediate whānau needs through provision of food at low or no cost | Community food organisations include

|

| Here 2 Help U (Wise Group) | Food as a gateway to connect whānau to health and social support | Here 2 Help U is an online portal that was developed in response to Covid-19 and the growing need for whānau to access health and social support when and where they needed it. Whānau can ask for assistance with a range of needs including meals or food parcels. The initiative uses food as a gateway for whānau to access support with other issues including physical health and mental health, in ways that are mana enhancing. Originally prototyped in Hamilton, the Here 2 Help U is now available in four regions. |

| New Zealand Food Network | Connected and centralised supply and distribution of donated and rescued food to community food organisations | The NZ Food Network (NZFN) works to increase the supply of food to community food services by distributing bulk surplus and donated food from food producers, growers and wholesalers through to food hubs around New Zealand on an ‘as required’ basis. By working with bulk supply, storage and distribution, NZFN provides a single national point of contact for businesses looking to donate food, and a coordinated supply chain that increases efficiencies in rescued and donated food distribution and utilisation. NZFN worked with iwi agencies and Whānau Ora organisations across Aotearoa to build marae into their distribution network and “get food to the door of whānau where others couldn’t” (John McCarthy interview). This led to the development of the Good Kai Network concept (see further below). |

| The Good Kai Network | Māori food sovereignty | The Good Kai Network is a by Māori, for Māori food system network that is under development with funding from The Tindall Foundation, in relationship with three Iwi. The initiative “utilises hapū/kinship groups and whānau land, local people, and community knowledge of food growing and harvesting…to support hapū and whānau to be more resilient in times when food is in short supply or unaffordable, at the same time creating employment and developing Māori enterprise” (The Tindall Foundation, n.d.) |

| Free Guys social supermarket (Kai Avondale) | Meeting immediate whānau needs via a social supermarket – local, affordable and accessible food choices | 'Free Guys' is a social supermarket where shoppers can access rescued and donated kai and products once a week. It operates on a ‘take what you need, pay what you can’ model. |

| Kore Hiakai Zero Hunger Collective | Advocacy to highlight the extent of food insecurity, its drivers and pathways for change Collaboration to support practice shifts and pathways for change | In 2019, the Kore Hiakai Zero Hunger Collective was formed by six NGOs (ACM, The Salvation Army, VisionWest, Wellington City Mission, Christchurch City Mission and Council of Christian Social Services) to eliminate food insecurity in Aotearoa. Kore Hiakai has a partnership with MSD and is connected to over 300 foodbanks and community food organisations across the country. Kore Hiakai is supporting systems change by driving collaboration and collective advocacy for change through the publication of research and advocacy papers, symposium. Focus areas have included income adequacy, the Aotearoa Standard Food Parcel Measure nutritional guidance, ‘Mana to Mana’ principles of practice for community food distribution. |

| Aotearoa Food Rescue Alliance | Food waste reduction Sector-wide capacity building of food rescue organisations | The Aotearoa Food Rescue Alliance provides national support to help build the capacity of local food rescue organisations to reduce food waste and increase food security. Their work is focused on building connections across the food rescue sector, sharing IP, best practice and learning, providing training, facilitating food rescue organisation set-up or expansion, enabling greater purchasing power for members and leading advocacy for government policy change. |

| Mana Kai Initiative (The Aotearoa Circle) | National food system strategy | The Mana Kai Initiative is a public-private collaboration involving all parts of the national food system – from growers, to NGOs, central government, businesses and consumers. Its aim is to co-design a national food roadmap that will support the development of solutions to systemic issues within the current food system. |

| Papatoetoe Food Hub (The Southern Initiative Healthy Families) | Circular food system – diverting waste food to create affordable local food | The Papatoetoe Food Hub is a community-led enterprise, within a circular economy model in which surplus food is rescued from being wasted and turned into healthy, culturally appropriate and affordable food for the community, within a zero-waste approach. The Hub employs 12 local people and supports local businesses and communities. It delivers on-site learning programmes and community events. The Hub operates a collective model with 16 other Food Hubs to offer mentoring and practical support. This model is viewed as a "replicable initiative that builds local food resilience by providing access to good, affordable and sustainable food, through rescuing and upcycling surplus food, thereby reducing food waste, waste to landfill and greenhouse gas emissions” (Trotman, 2021). A story about the initiative highlighted a range of system change outcomes including policy change (e.g. Auckland Council Long-term Plan), community-led food enterprise and food sovereignty, diverse collaboration and partnerships, inclusive and mana enhancing food experiences and modelling of regenerative practices. |

| Te Waka Kai Ora | Māori food sovereignty Sustainable food systems Mātauranga Māori | Te Waka Kai Ora is the National Māori Organic Authority of Aotearoa, a non-profit organisation that acts as kaitiaki for the Hua Parakore Indigenous Validation – the world’s first Indigenous verification system for Kai Ātua or Pure Food (food that is free from genetic modification, nanotechnology, chemicals and pesticides and congruent with Māori cultural practices). The system is based on mātauranga, tikanga and te reo. It validates Māori growers, producers, cooks, bakers, fermenters and farmers and enables them to “tell a kaupapa Māori story with regards to their food production” (Te Waka Kai Ora, n.d.). Te Waka Kai Ora provide a kete of resources to validated and verified producers to support their practice across the six kaupapa of Whakapapa, Wairua, Mana, Māramatanga, Te Ao Tūroa and Mauri. Te Waka Kai Ora also had a partnership with tertiary provider Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi (n.d.) to offer a L3 certificate in Kai Oranga, teaching whānau to grow their own food whilst rebuilding “knowledge relating to traditional and contemporary food, sustainable practices, food production and management (kaitiakitanga) back into whānau, hapū and iwi settings”. This is currently on hold due to funding constraints including the need for students to access resources including gardens in urban settings. |

| Papatūānuku Marae | Sustainable food systemsMāori food sovereignty Mātauranga Māori | Papatuanuku Marae is a hub of sustainable food and food sovereignty initiatives. This includes:

|

| NZ Food Waste Champions 12.3 | Food waste reduction | NZ Food Waste Champions is a coalition of representatives from across the food supply chain, championing Aotearoa's progress towards halving food waste by 2030 in alignment with the Sustainable Development Goal target 12.3. The coalition focuses its efforts on showcasing best practice, government advocacy and events and campaigns. In mid-2022, the coalition plans to launch a business commitment for waste reduction. |

| Koanga Institute seed bank | Food sovereignty Regenerative food systems through education and capacity building | Koanga Institute is a non-profit organisation based in Wairoa seeking to support food resilience and communities self determination through protecting and developing heritage plants, researching and sharing knowledge of regenerative food practices. The Institute has brought together NZ’s largest collection of heritage seeds (800+) over a 30-year period. It has an online knowledge bank to share learning about regenerative practices including seed saving, growing nutrient dense food, maramataka and food forests. |

| Future Food Aotearoa | Food tech and future food system innovation | Future Food Aotearoa is a movement of future food and food tech company founders that is committed to building a more future focused, healthy ‘principled’ food system that delivers commercial viability alongside other impacts (e.g., health, food sovereignty, Māori economic development). Future Food Aotearoa is focused on harnessing founders’ collective learning, expertise, shared values and purpose to grow the future food ecosystem. The vision for this movement also includes the development of a growth incubator to support companies in securing capital and getting their products to market and scale. |

| EnviroStrat - Greenwave | Regenerative food systems that support regional economic wellbeing Māori food sovereignty | Greenwave is global initiative brought to NZ by Envirostrat and AgriSea, creating a disaggregated seaweed supply chain where local producers establish seaweed farming in rural communities and supply a centralised agent that removes some of the initial capital outlay for suppliers to enter the value chain, and manages marketing and R&D. Alongside environmental benefits of adopting regenerative farming practices, the goal is to create new economies that drive regional wellbeing by creating resilient jobs. |

7 Appendix 2: Participant acknowledgement

Thanks to participants who gave their time and knowledge to contribute to the development of this report. Participants represented Foundation North, The Centre for Social Impact, The Tindall Foundation, Auckland Council, Te Pūtea Whakatupu Trust, and The Good Fale and Rākau Tautoko as part of The Kai Collective.